Replanting the Family Tree

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

"Louie? The doctor will see you now. Please proceed to room four," beeped the computer in the waiting room.

He placed his phone into his pocket and walked down the corridor. There was a bit of eeriness as the hallway was empty. The other patients were in their own rooms, getting their own exams.

Perhaps the eeriness was all in his head. He had received a message following his checkup last week. There was something that his doctor needed to speak to him about, and it was evidently serious enough that he needed to return in person. What was the matter?

He had just managed to sit down in a chair when Doctor Webb entered.

"Louie, it's good to see you again."

"Look doc, just tell me directly. I've got too much anxiety about this."

"Oh, I apologize for getting you worked up. We just ask patients to come in for brief chats. It's standard policy."

"Then is it not serious?"

"Look, here's the thing. Your blood tests show that you have sickle cell anemia. This isn't too serious. We have treatments available for you."

"What kind of treatments?"

"There's gene-editing techniques that can be employed. We modify genes in your bone marrow and replace them. After a full treatment you should be fully cured."

"Oh, that's it?"

"Yeah, it's really not too serious for people today. It's easily treatable."

"Okay. Thanks. I guess this didn't take too long."

"Not at all. Please speak to the receptionist about scheduling your treatments."

"Doc, just one more question. Isn't sickle cell anemia something that mainly affects black people?"

"Mainly, yes."

In the lobby, he tapped his phone against the receptionist's large computer monitor. Instantly the two began to communicate, negotiating availabilities and deciding on a set of dates that worked. In just about fifteen seconds his phone dinged, letting him know everything was set.

In the back of his head he began to question things. He was not black, far from it, so how did he develop this disease? His doctor didn't seem to question it, so it must not have been that important. Yet he couldn't let this go.

On his way home, he stopped at the pharmacy. There he picked up one of those boxed DNA kits. It was cheap, but something he had never considered before.

It had been a fad when he was a kid, but that had died down afterwards as DNA tests became more professional and useful in the medical industry. Suddenly the cheap kits you could buy didn't seem good enough for professionals to use.

Accuracy aside, he had to know.

The kit was simple to setup. First he had to plug the kit hardware into the wall. A small LCD screen lit up excitedly and showed an arrow downward. That was where he had to put the vial.

The box seemingly didn't include a needle, so he had to grab one from his sewing kit. With a thin prick a small speck of blood began to drip from his finger. He placed his finger over the small vial until it reached halfway. There was a marker on the vial telling him when to stop.

He placed the tube into the machine and it began to process automatically while he went to his bathroom to get a band-aid.

To his dismay, the test was taking longer than he had thought. He looked at the instructions on the box again. Results would be available in ten hours or less. Great. He looked out the window and saw the bright full moon overlooking the park. It wouldn't be until he woke up that he would know.

He had trouble sleeping that night. There was something strange about his family history, something he never knew, and he had to get to the bottom of it. What an odd feeling, your identity being unclear. He thought he knew who he was, but clearly he was wrong.

Morning came quickly. He opened his eyes widely and looked over at his phone. It was only 7am. His alarm wasn't set for another hour. Still he hurried out of his bed and into the kitchen where the device reported success.

He tapped the phone against the machine, which then downloaded the results and made them available through a website.

What he read on the site was not what he was expecting. His parents were French and Belgian, which he had known. But what was more interesting were the genes traced back to Libya. It was a smaller percentage, but not zero.

Had the disease skipped several generations and manifested itself in him? Why was this something he never knew?

He initiated a call with his parents. They had to know more.

"Louie? It's seven in the morning," his mom groaned as she rubbed her eyes.

"I got one of those DNA tests last night. Did you know I'm partially Libyan?"

His mom looked just as bewildered as he did.

"Dear, who is calling so early?" he could hear his dad say off to the side.

"It's Louie."

"What does he want? Doesn't he know how early it is?"

"He says he's Libyan?"

"Hand the phone over to me."

"Dad?"

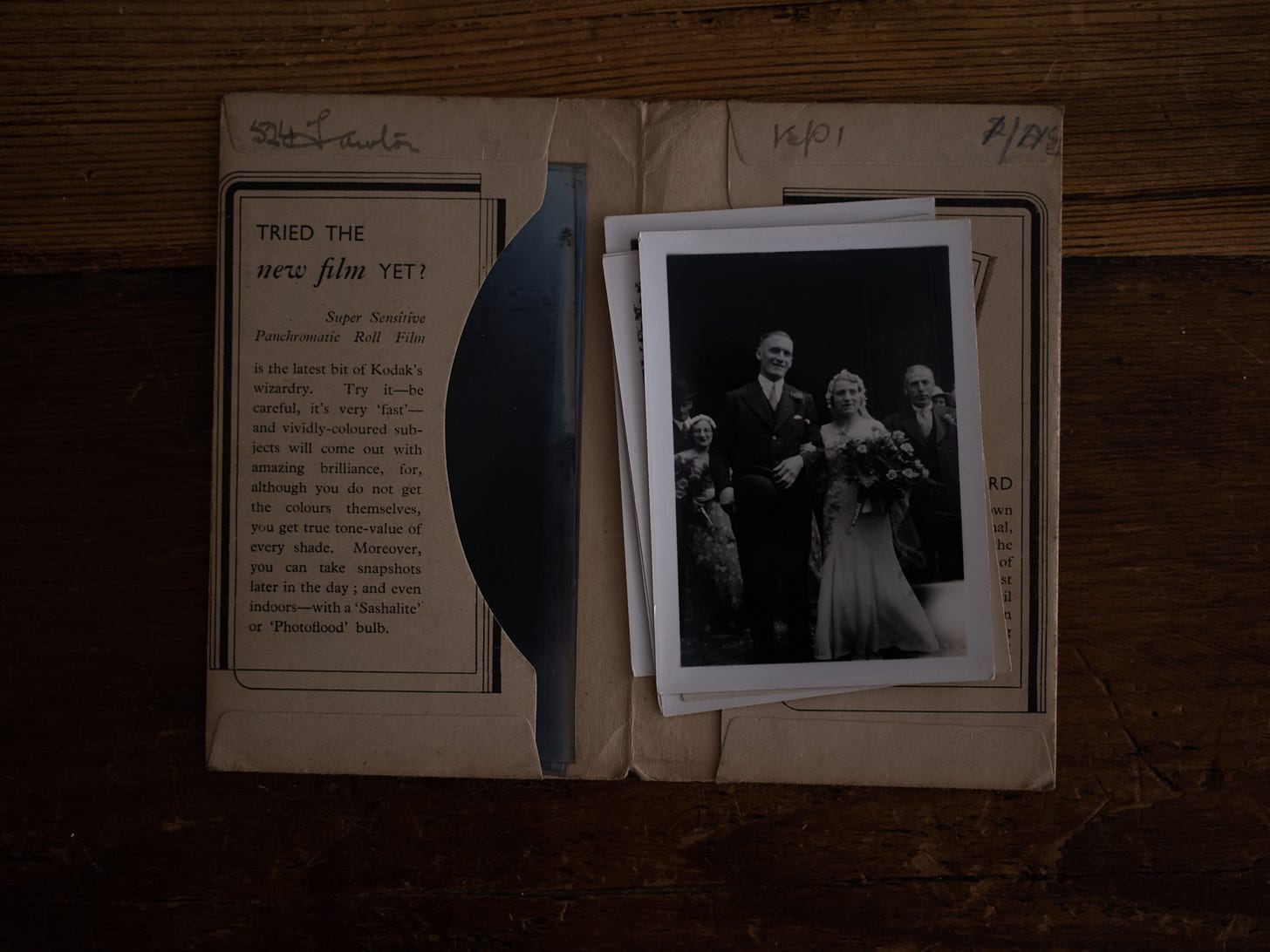

"Louie, your grandfather, my father, was from Libya. He was just a bit older than you when there was a long conflict with Chad. He fled the country before the ruler would've forced him to serve. He arrived in Italy as a refugee and they took him in."

"I never knew that. I just assumed he was Italian."

"He was welcomed generously by the Italians. That was where he met his wife and where he managed to settle down. I was born not too long after that and I eventually moved out here."

"He never talks about it."

"He never told me either. He's from a different generations, where you didn't talk about the horrors of war and leaving your home country."

"You never told me about this either."

His father sighed.

"I didn't know how. It wasn't really my story to tell either. I was hoping that my father would open up about it one day, but he's continued to bury his memories of growing up."

"Huh, I didn't think about it like that. I wish there was something I could do for him."

"I wish so too. But sometimes you need to accept your own limitations and do the best that you can for others."

"That's true. That's very true," Louie mused.

"Why did you call so early? And why did you take a DNA test?"

"I got blood work done last week, as part of my checkup."

"How did that go?"

"Alright. I was diagnosed with sickle cell."

"Isn't that treatable now?"

"It is. I was just surprised that I would've gotten it."

"I guess it was passed down from your grandfather."

"Does he have it?"

"I think he did have it at one point. Again, he hasn't really shared much with me or even with your grandmother."

"Perhaps I should call him. It'll give the two of us something to talk about."

Enjoyed this story? Get a discount on a premium membership, which grants you access to more stories.

So I know that my depiction of sickle cell anemia here is fairly inaccurate, but it was in pursuit of telling a story.

The one aspect that isn't inaccurate is the ability to treat and ultimately cure the disease. That's not even futuristic anymore, as CRISPR-based gene-editing has shown incredible success in clinical trials.

This is a disease that is relatively common among black populations, and primarily in sub-Saharan Africa. But we've made some amazing strides in treatment thanks to our new ability to provide these kinds of precise therapies. It's an exciting time to be alive, and it makes me wonder what other kinds of genetic diseases can be easily treated.

Though the second half of the story is really more about this idea of identity. From this I am inspired by the story of Harry Pace, told in the serialized The Vanishing of Harry Pace from Radiolab. Louie's grandfather would likely be considered black given his origins in Libya, but his relatively light skin would him look similar enough to Italians that one wouldn't tell.

In this story, he is a refugee fleeing the Chadian-Libyan Conflict and ending up on the shores of Italy. The topic of refugees in Italy is politically charged today, although it shouldn't be. Refugees can be valuable additions to a community and a culture and we should embrace not just the moral argument but the economic one too.