The Carbon Dioxide Farmers

Pelin took a deep inhale, a habit he picked up long ago as a way to taste the air. There was no point anymore though. The air always had the same taste: recycled, mildly stale, with a faint aftersmell of ozone.

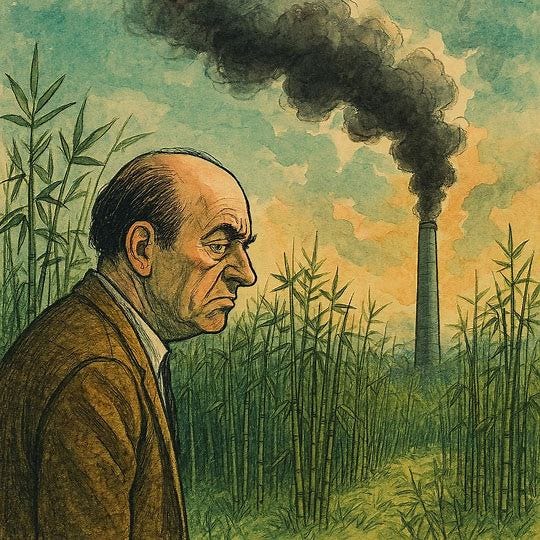

The voice of his civil engineering professor echoed in his head; he was a man who saw every ton of carbon dioxide as a mortal sin against the planet. He had believed him when he was a young student, someone who saw the world in black and white.

Now Pelin managed this grand machine in an even larger grand system. From his perch on the observation deck, he could see the Kindling Fields sprawled out a hundred feet below him.

Down there, in the crisp morning air, robotic sweepers passed back and forth on large treads. Their many articulated arms plucked fast-growth bamboo from the ground and algae from various pools and deposited them into the hungry maw of the Generation Stacks. Ten of them stood back to back like massive chrome ducks, each one seeking its breakfast.

Smoke rose into the sky after being intensely scrubbed. The CO₂ was collected before it even touched the open air, creating a thick and black crust on top of the stacks.

“It must’ve been strange, sir.” commented Zara, the new intern.

He could see her reflection through the chrome stack. She looked like an earnest ghost, but her eyebrows were raised in a way that showed she was having trouble grappling the reality compared to the theoretical knowledge of the classroom.

“This was once the enemy, wasn’t it?” she continued, looking up at the tall stacks. “Carbon dioxide was the villain of the Great Warming. Everyone said we had to get rid of it.”

Pelin lifted the aluminum can to his lips and took a long sip of his soda. It was hyper-carbonated, a direct byproduct of what they did here. The sharp hiss of it was the sound of his paycheck. It tasted like his daughter’s tuition fund. He swallowed, feeling the sting as it went down his throat.

“Well, we were taught that the our system was unbalanced. We had way too much carbon and it was cooking the planet. But as I realized when I got older, too little starves the economy.”

He gestured with his can towards the thin pipelines snaking out from the stacks like veins on their way to the city beyond the exclusion zone.

“When I got married, people still dug diamonds out of the dirt. Natural stones.” Pelin swirled his soda, his eyes following the lines of the pipes. “Now, you’re wearing atmospheric feedstock. Your uniform, the carpets in the arcology, the very bones of the city… it’s all built from what we catch. And the catch only stays good if the supply of carbon is predictable.”

Zara nodded and tried to process. She looked out towards the horizon, where a small drone was projecting a flickering protest sign in bright blue light.

“I talked with my history professor about this, before the semester ended,” Zara said, her curiosity growing. “He called it the ‘Great Irony’. Your generation was taught to save the world, to reach zero emissions, and now you’re paid to manage their release.”

Their conversation was interrupted by a soft buzz from Pelin’s smartwatch. He looked down at the glowing screen with a new sensor reading.

Atmospheric density: 198.2 ppm.

Status: Below Optimal Harvest Threshold.

Recommendation: Increase Generation Output by 3.0%.

Almost unconsciously, he flicked his thumb across the screen, authorizing the burn increase. A low, hungry roar rumbled through the floorboards as the stacks inhaled deeper, a mechanical growl that felt like a physical weight on his chest. He knew what would happen, even if he didn’t check to confirm. He heard the whirring from the fields deepen half an octave as the robots accelerated and the combustion chambers flared a tad hotter.

He turned away from the window, looking away from the protest drone and Zara’s questioning gaze.

“Let me give you your first lesson here,” Pelin said, his voice steady yet weary. He took a final, long sip of the hyper-carbonated soda, letting the familiar sting of the byproduct settle in his throat. “The system needs what the system wants. Your job isn’t to ask why. Your job is to make sure the numbers from the input match the output.”